For spring break from my daughter’s school, the three of us joined our friends Dave and Sinee on a trip down to San Antonio, Texas, where Pete and I used to live before having Olive. Neither of us had been back for fifteen years, and Dave and his daughter never at all, so we were all essentially tourists, and did all the touristy things I never managed to do in my five years as a resident: boat shuttles on the riverwalk, SeaWorld, the Alamo.

Except for my classwork, I’d been painting exclusively still lifes, and I was excited to use the opportunity of outside time in a colorful city to take some photos to paint from. As I’ve mentioned, I’m a fan of Carole Marine, especially her street scenes, and I wanted to see what I could do with similar subject matter.

Once I got over my initial self-consciousness of feeling SO touristy (taking photos from a tour boat on the Riverwalk? Could I be any more cliched?) I did take some interesting pictures, though most wouldn’t work for my purposes:

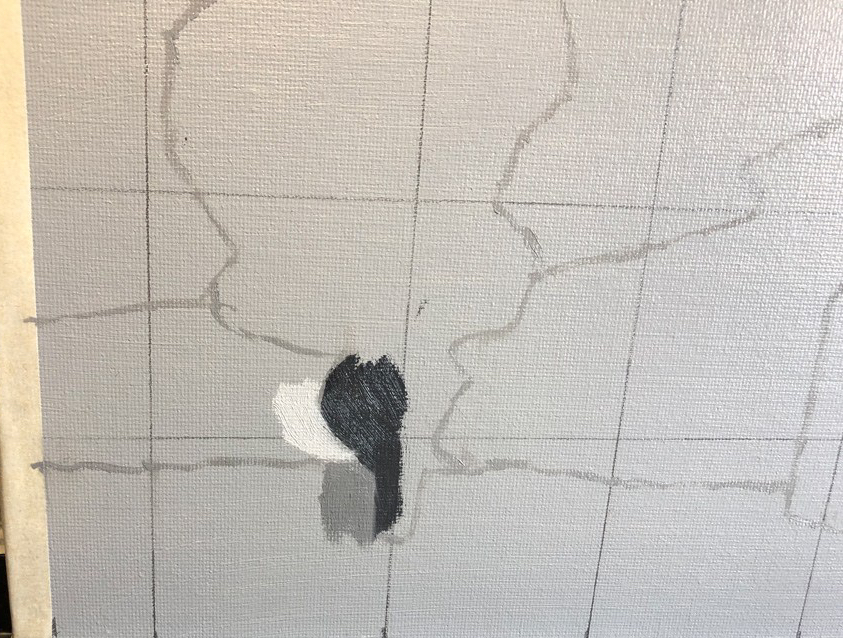

Unfortunately, I rarely take photos, and I wasn’t aware that when I zoomed in to get a good simple image with my iPhone 6, I’d end up with something like this:

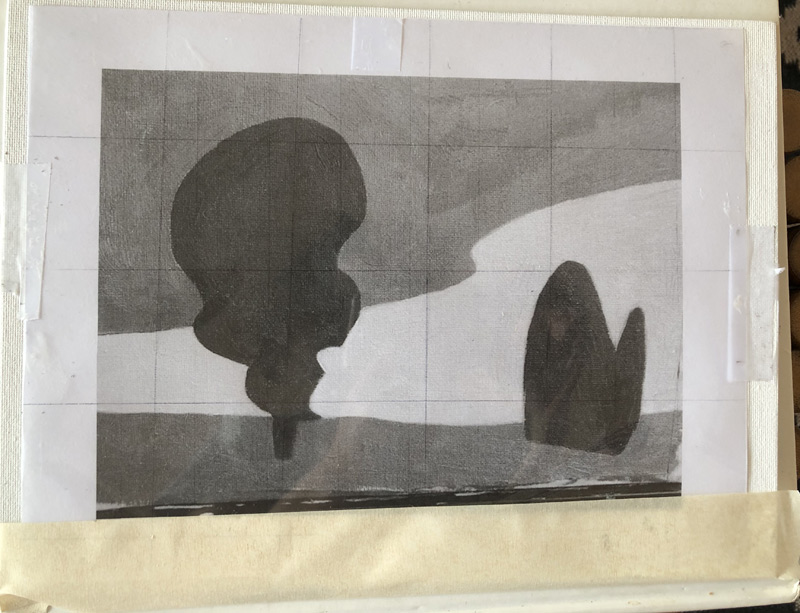

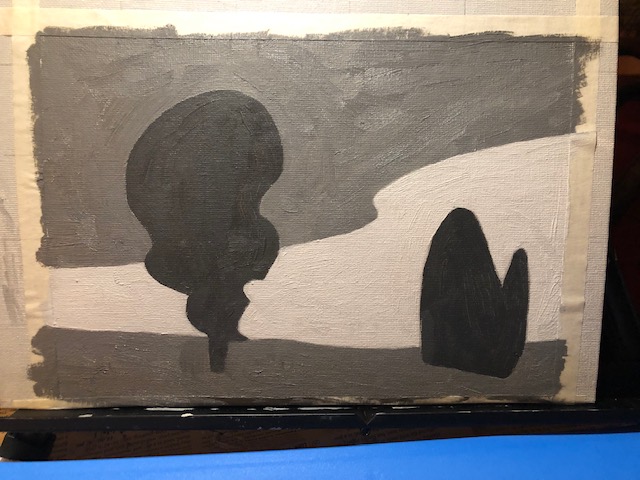

When we got back from our trip, I printed out a few of the more simple ones to try (I’ve since realized I didn’t need to have a hard copy — I could just have them open on my laptop. So much easier!). First, though, I bought Carole Marine’s ArtByte tutorial on painting people. The tutorial was so simple to follow, and –like Bob Ross before her — she made it look incredibly attainable.

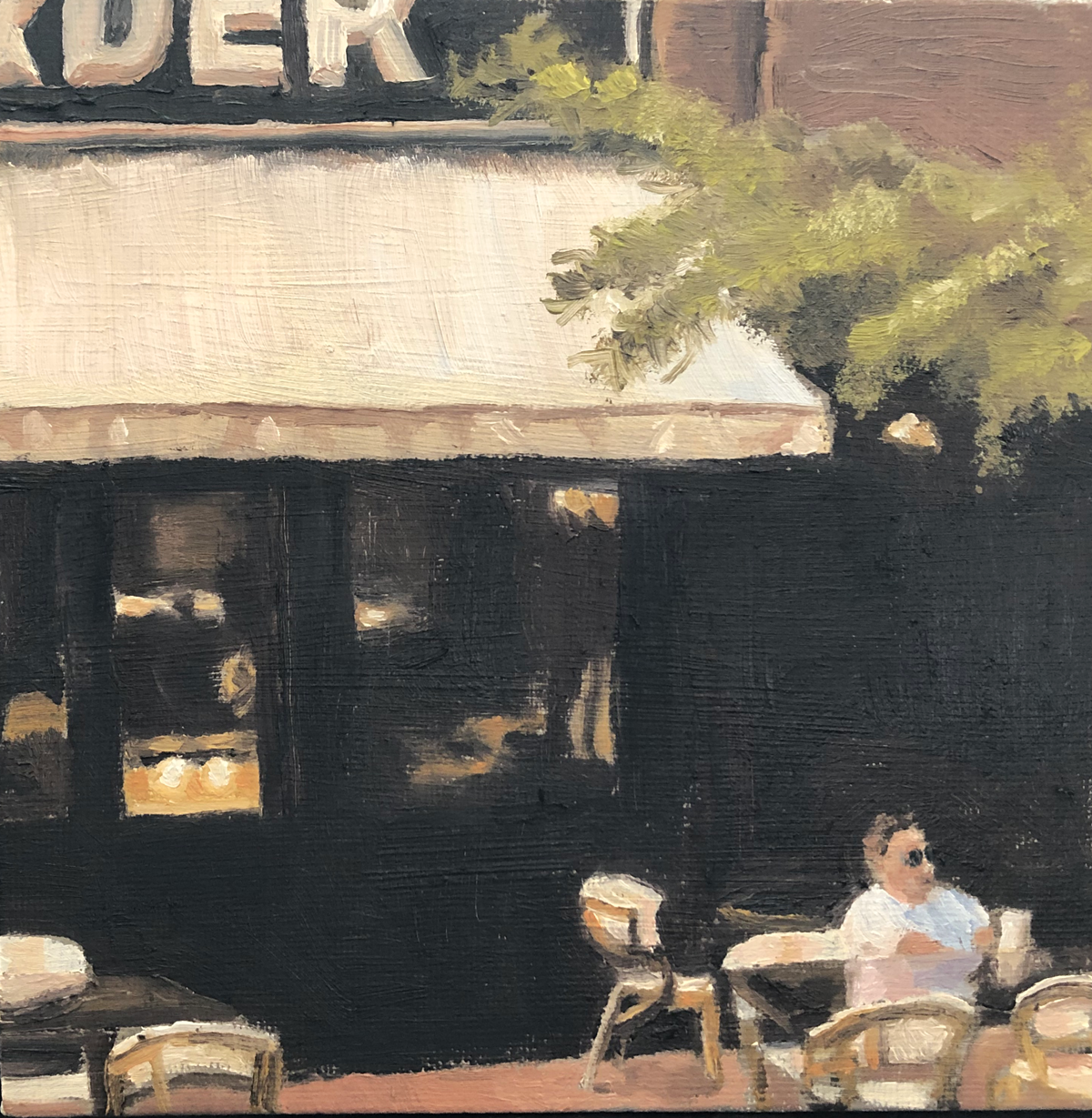

Here’s my attempt:

I’m pretty sure that where I went wrong here was in attempting to do too much in a very small space. This was only a 6″x6″ canvas, which makes the guy, and all those little chairs less than an inch high. Looking at Carole Marine’s street scene paintings again, it does look as if she limits herself to a smaller number of larger-sized people when she’s painting her small canvasses, because this kind of expressive painting just looks messy at a small size.

I also found that at this small size alla prima was really limiting. In fact, I’ve been thinking that my attempts at Daily Painting — completing a work in a small period of time, hopefully fairly regularly (though not daily) — are hurting rather than helping. When attempting to paint the details of the chairs, they were so tiny and the paint was still so wet, that it was nearly impossible to neaten it up and make my colors work the way I wanted. It would’ve made more sense to put this down for a few days and come back to it when it had dried enough to finesse it, but I felt pressured by the Daily Painting credo. I’m also wondering if attempting to paint expressively is right for me right now — I think I need to focus on trying to learn the rules before I break them!

Some rethinking to do…