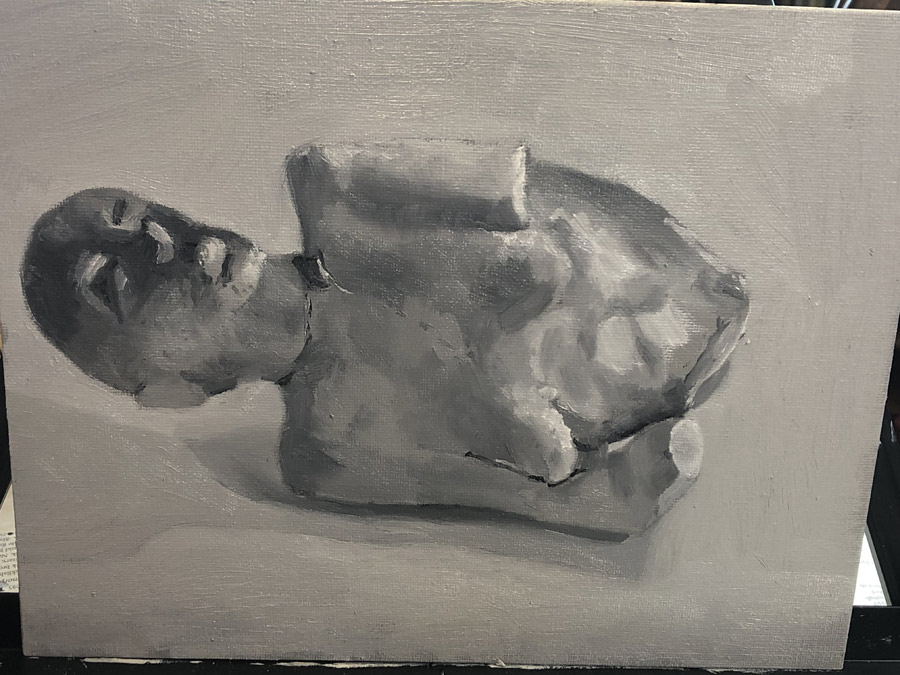

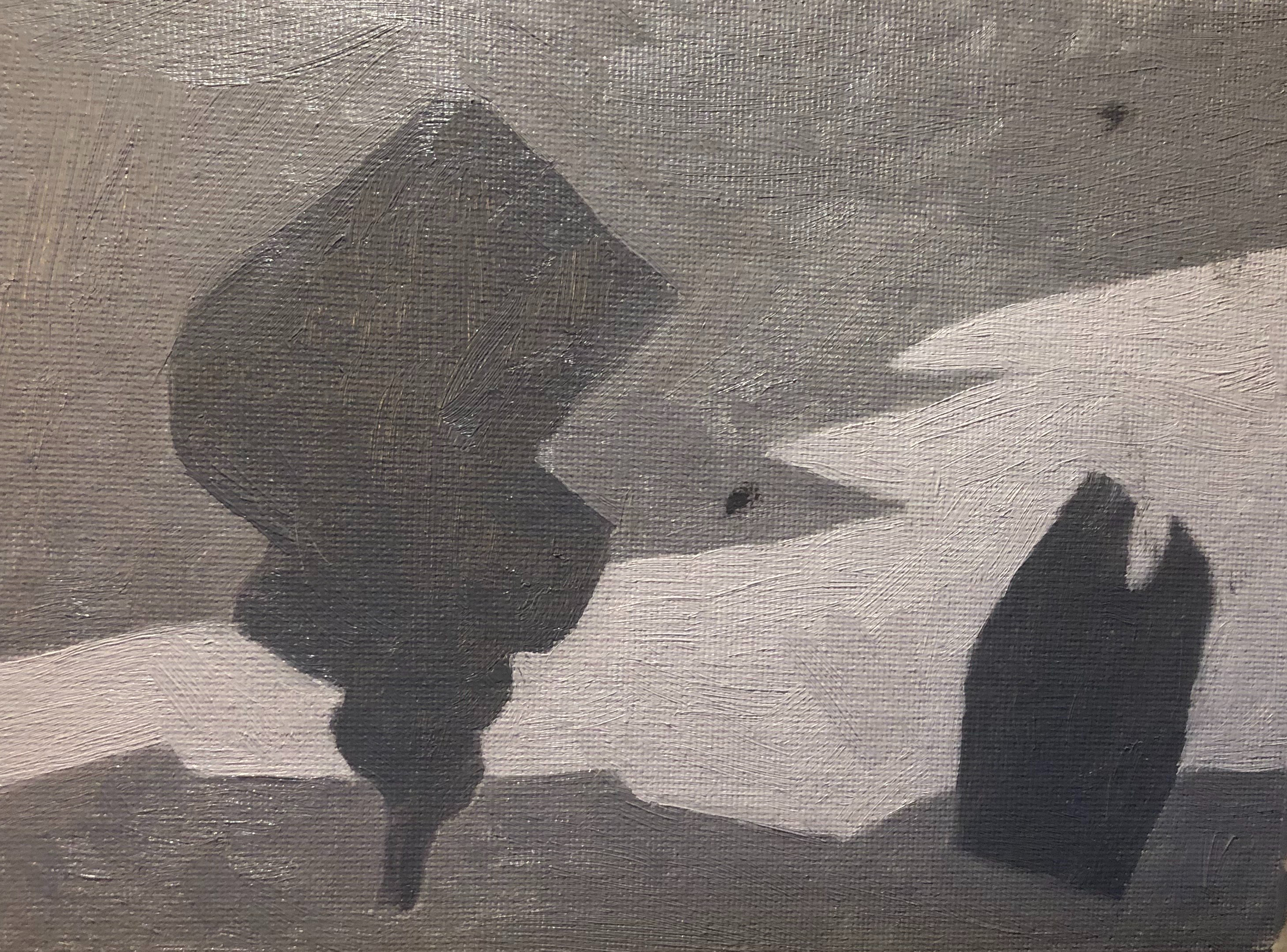

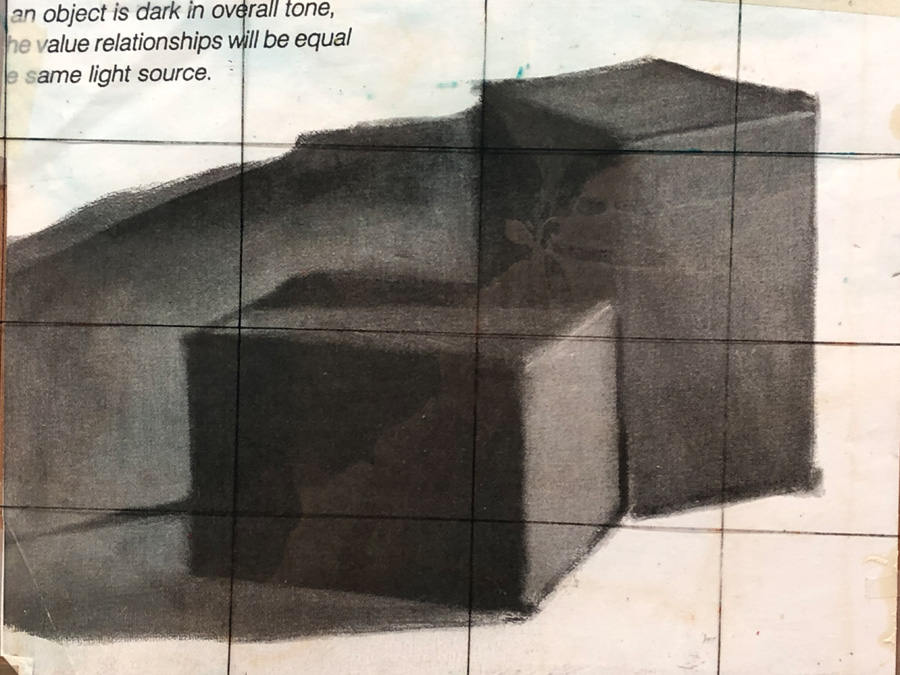

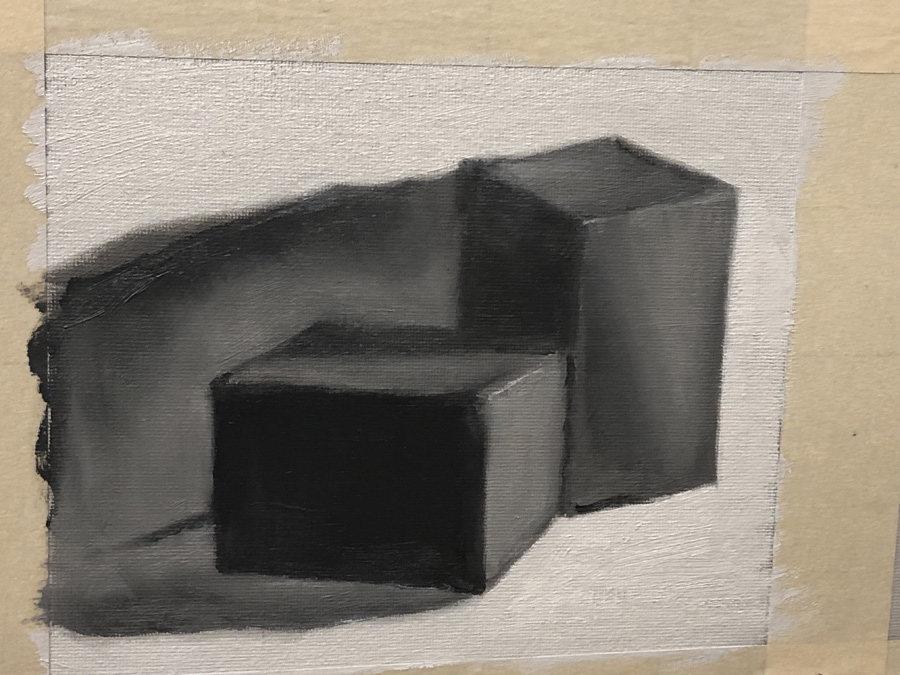

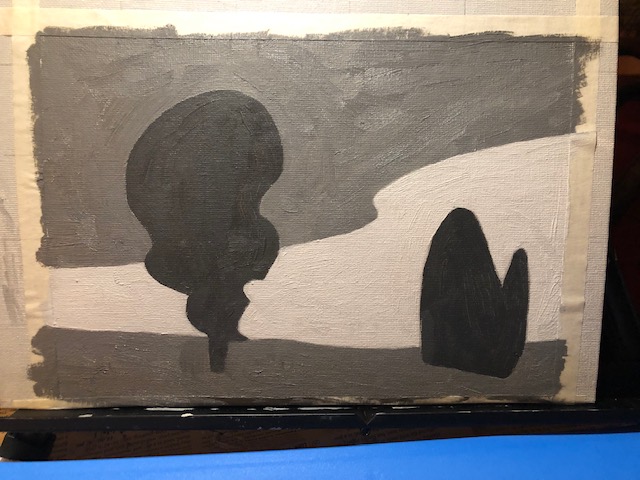

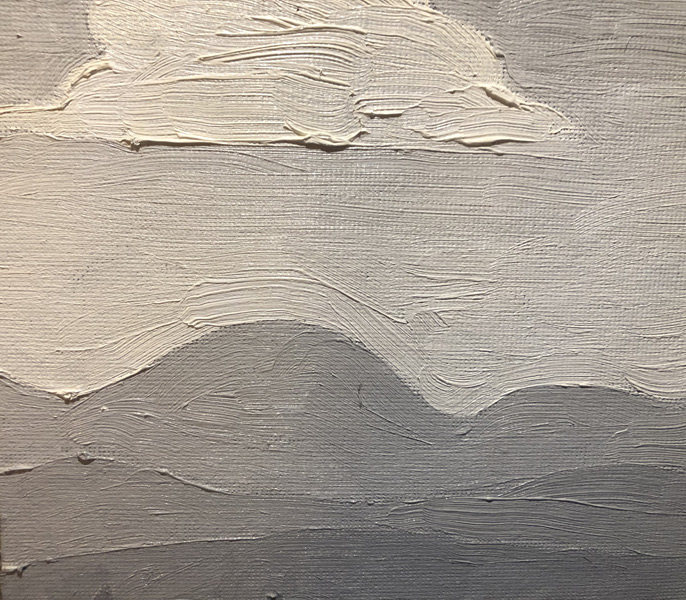

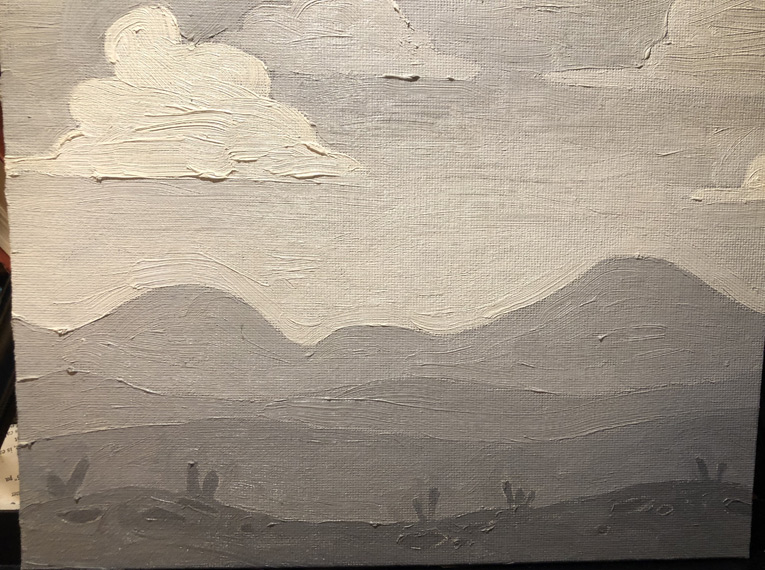

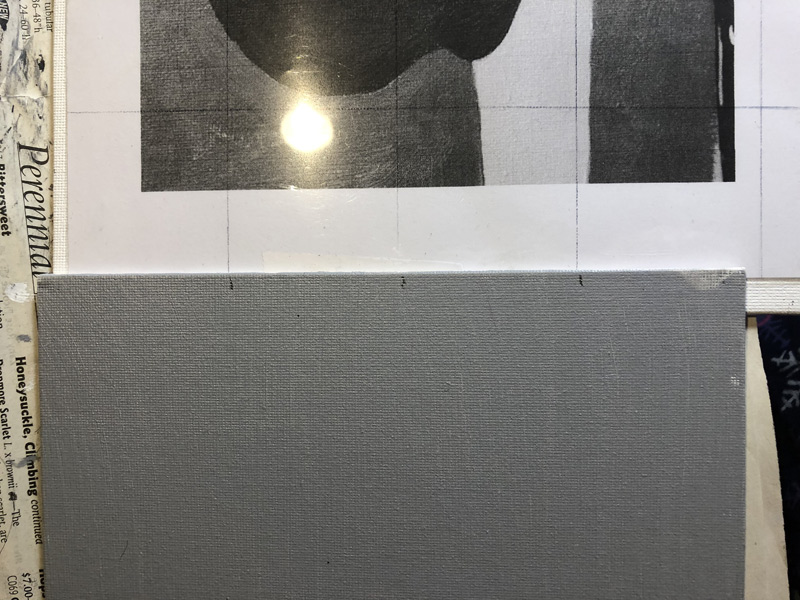

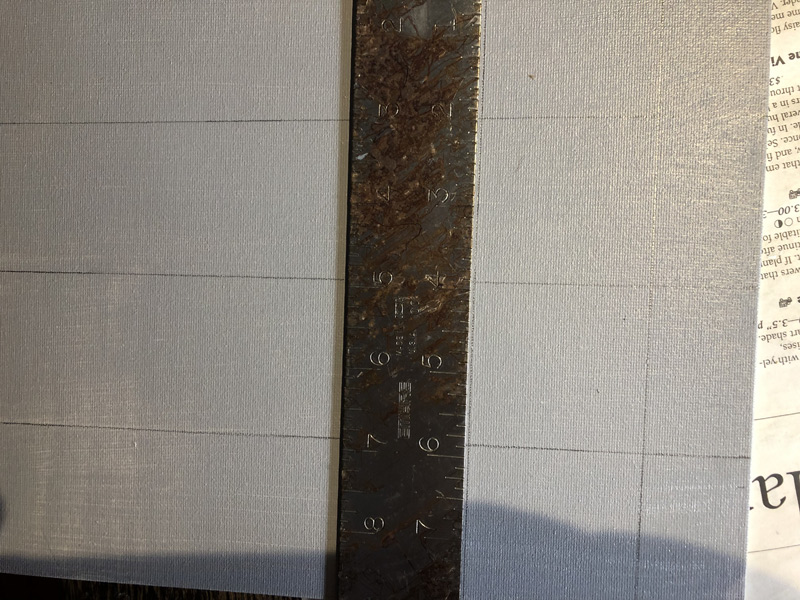

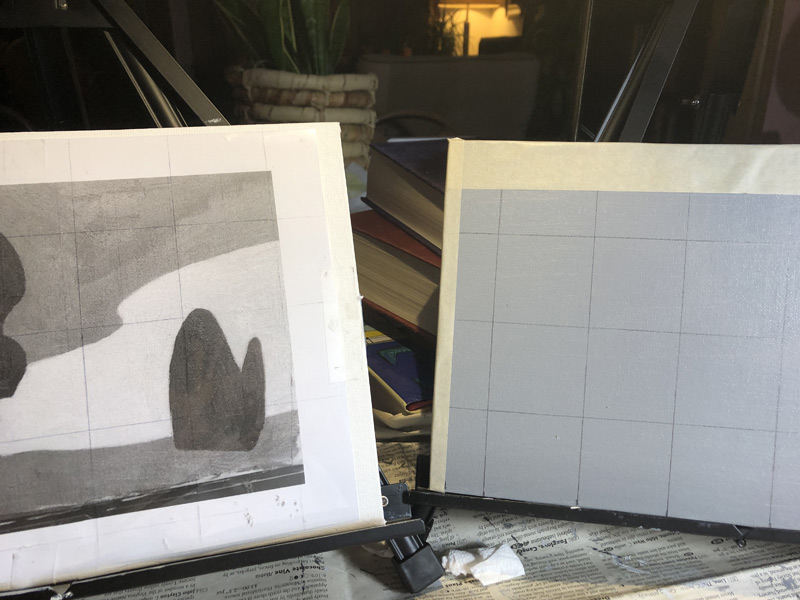

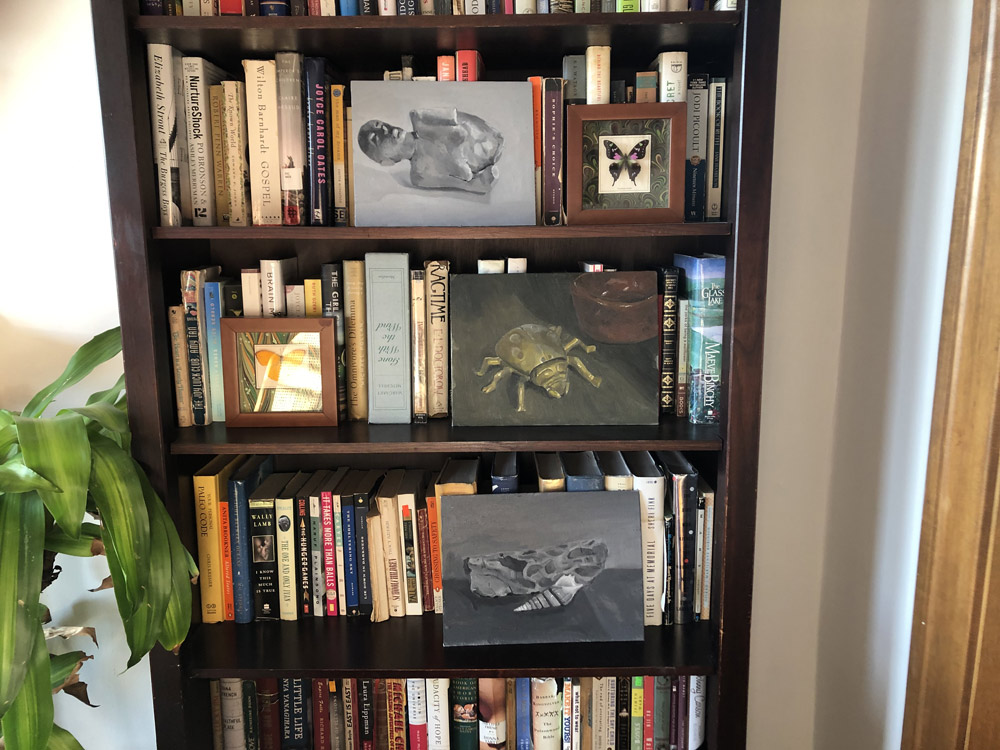

We’re still at the stage where all of our paintings for class have been in shades of grey: grey oven mitts, grey boxes, the beginning stages of grey horse heads (more on that to come). It makes sense — people perceive value before color, and mastering that in greyscale is much simpler and less distracting — but man, is it boring. Until now, I’ve been faithful to the method, figuring that painting one more grey oven mitt was just like Ralph Macchio waxing Mr. Miyagi’s car, but when I sat down to paint on Saturday and remembered I had run out of Portland Grey Medium, temptation got the better of me. I had recently been to a neighborhood estate sale, and had bought a big case of oils for $5 (to give you a better sense of the quality of these paints, they were mixed in with a bunch of Bob Ross acrylics), so figured what the hey, why not?

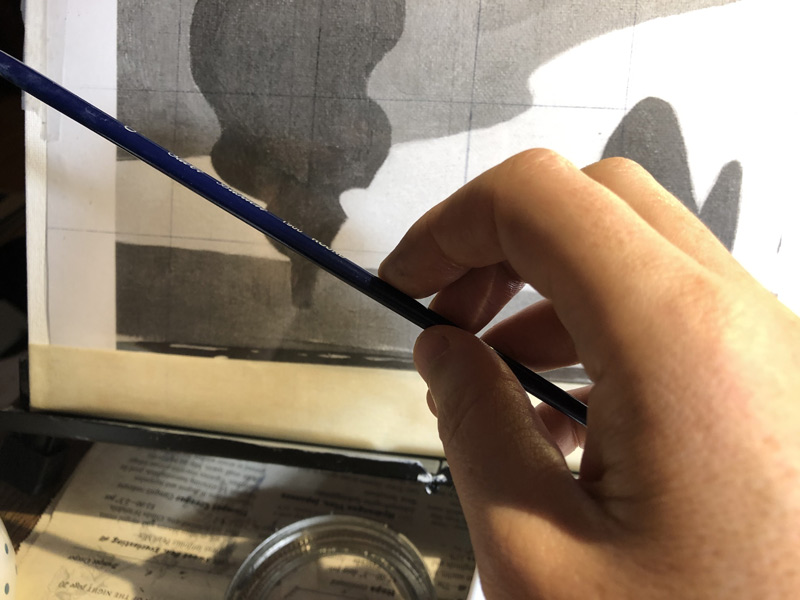

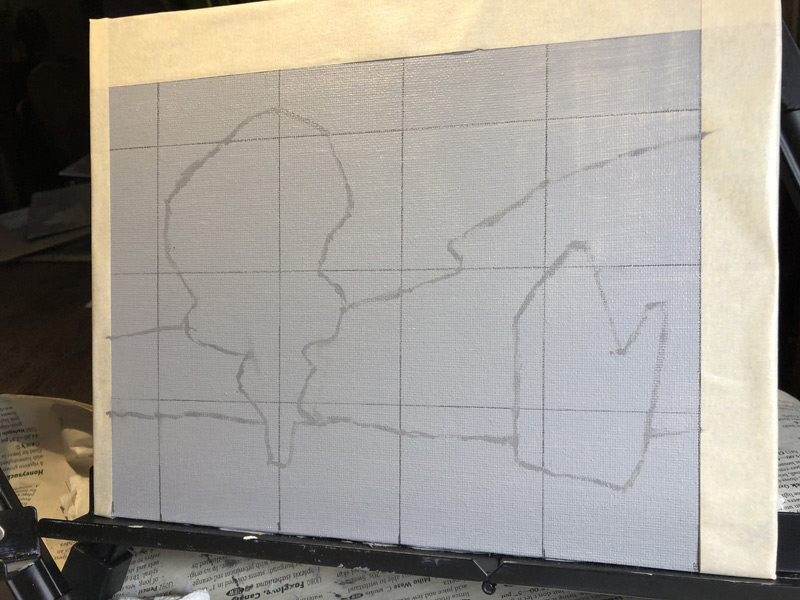

Good Lord but this was tough. There’s a reason, I’m learning, that people start out with less precise objects like apples and pears: Unless your apple is turquoise and shaped like a banana, it’s almost difficult to make an apple look unnatural — there’s so much acceptable variation. Not so with a machine-made, perfectly symmetrical brass ladybug sculpture with legs poking out every which way: You might not have ever seen one before, but you know what it’s supposed to look like. I drew and wiped off three times before I measured my way to a shape that was even remotely reminiscent of my model.

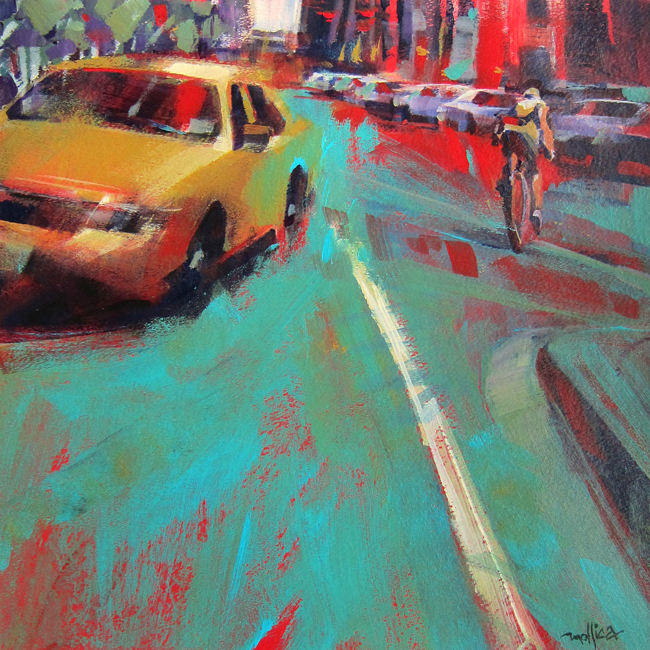

As I’ve noted, I’ve been reading Carole Marine’s fabulous “Daily Painting,” and one thing she mentions is that she mixes almost all of her paint from three colors: Cadmium Red Light, Cadmium Yellow Light, and Ultramarine Blue. This seemed like an easier way to go than trying to get a sense of the dozen or so paints in my new box, and I didn’t have any other instructions to follow. Instead of simply adding black to a color to make it darker, she typically “greys” the colors she wants to recede, adding different combinations of the three basic colors to make them less saturated. So in this case, since my brass was primarily yellowish, I used mostly Cadmium Yellow Light with a speck of the other two colors for the brightest yellow, and then darkened them further with more red and blue as necessary. My darkest tones are really more of a dark olive green. But — I’m a rookie and this is a rookie painting, so why would you listen to me? Go experiment!

My biggest issue, once again, was light. Not only did the light on my model change throughout my session — making it look entirely different — but I had a bright florescent clamp light pointed directly on my canvas the whole time I was painting. To me, the colors I was using looked vibrant and alive, until I took away the light and…

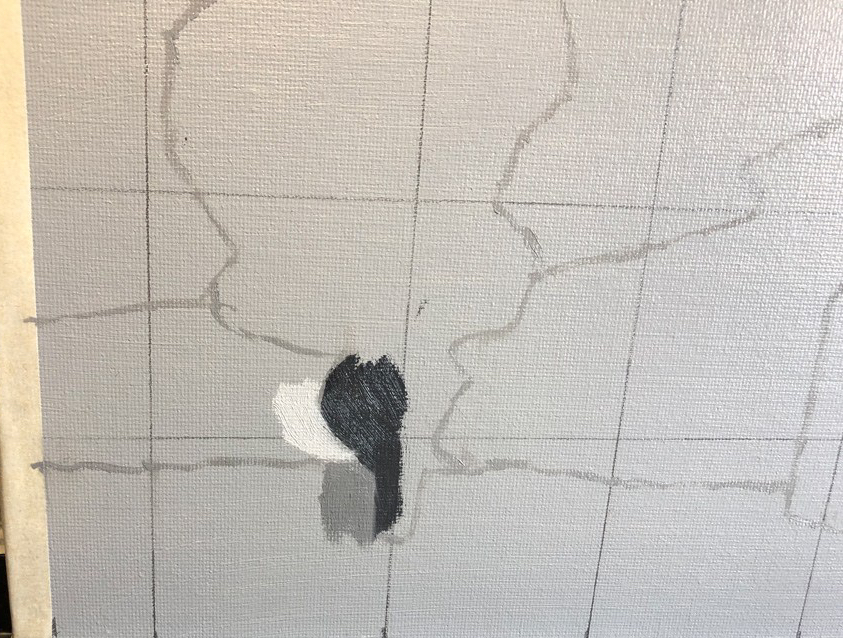

Well, you see. (Or maybe you can’t — it’s over to the right….a little higher….)

I’m finding as I’m painting on my own that I’m breaking every rule we’re being taught at the school. Fat over lean? Bah! Carefully painting patches of color rather than shapes? Well, that one I should do — but I haven’t been. Shapes all the way. It’s been one thing to follow the correct procedure when I’m painting oven mitts and boxes, but a whole lot more difficult when painting something as complicated as this bug turned out to be. Besides, Carole Marine says she paints her backgrounds last, choosing her order based on the saturation of the colors, so perhaps there are other “correct” procedures as well…. So much to learn!

Things I did well:

I think I did a decent job capturing the way light fell on each object

My bug has decent (though not perfect) proportions and looks three- dimensional (though I do see that the line down the center is off and the right front leg is too wide)

Put a bit more thought into the composition so everything isn’t simply centered

My little pinch pot has a decent texture and shape and was painted fairly quickly

Things I could improve

Too dark!

Background was once again an afterthought — basically thrown together from my leftover paint. Should start thinking about using different brushstrokes and hues to make backgrounds more interesting