In my last post, I wrote about programs that have helped me begin to overcome the main challenge in learning to draw: understanding form in 3-d space. In this post, I want to give a shout out to my absolute favorite resources in a bunch of different categories. And hey, if anyone’s reading this and wants to share theirs as well, please do!!

Anatomy

Proko’s anatomy classes are da bomb, no doubt. But for me, the benefits of them were the model poses (and subsequent draw-alongs) and the e-books. Sure, I’d watch the videos, and they were cute and sometimes laugh-aloud funny — but I don’t really learn that way. I’d watch them once, but any information I absorbed was really through the e-books — videos are simply too fast for my middle-aged brain. Sometimes, unfortunately, the e-books didn’t show enough different poses to make me understand (especially with the forearms — don’t know what God was thinking with those things) and in those cases I needed other references. I have lots of anatomy books, but the ones I find myself referring to most often, are:

Artistic Anatomy by Paul Richer and Robert Beverly Hale. Honestly, this is less of a shout-out than a half-hearted mumble. I don’t particularly like this book: Most of it is text (I wonder if anyone, anywhere has ever read it?), and the limited number of drawings at the end are really grainy and, again, limited in number. BUT every muscle is labeled, and we do see at least a few different angles of each body part, making it the best book I have for looking up a particular muscle by name. If anyone knows of a better one, though, do tell.

Morpho, Simplified Forms by Michel Lauricella. This is a teeny tiny book of unlabeled sketches of different body parts, with muscles broken down by group rather than individually. When I have trouble getting my mind around the shape of something (such as those dang twisty forearms), it’s been helpful to refer to this to see it broken down into its, well, simplified form.

However, my most favorite of all anatomy books is:

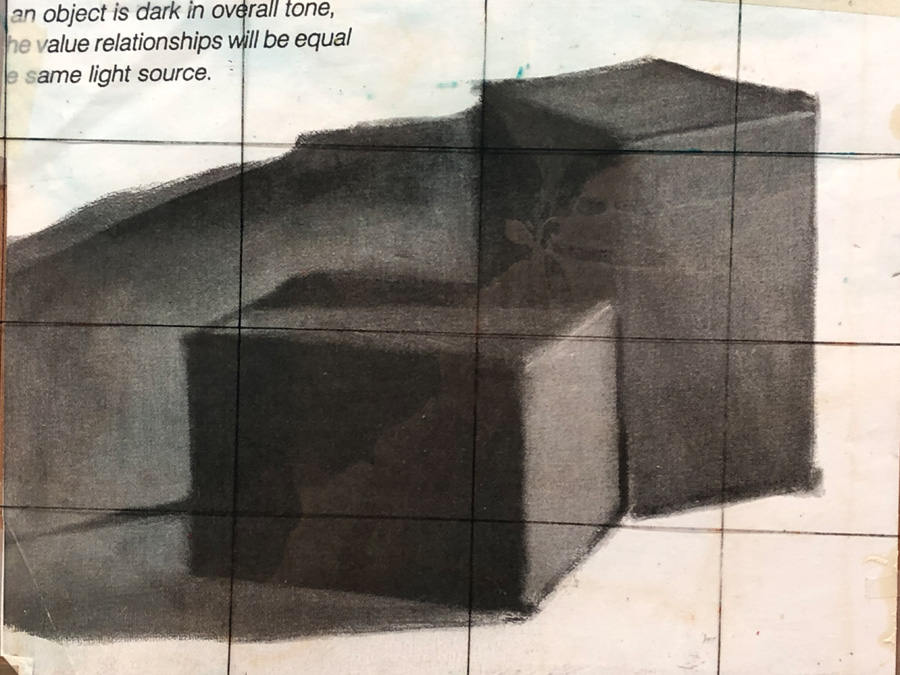

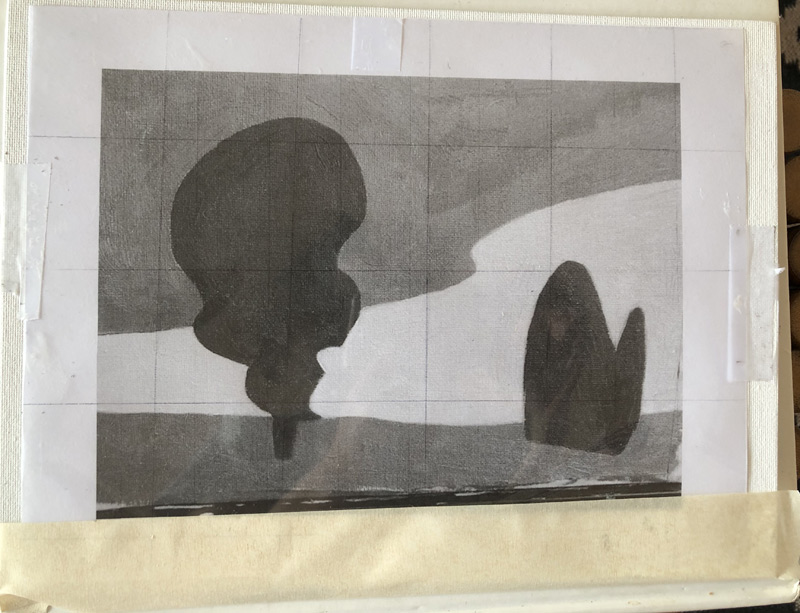

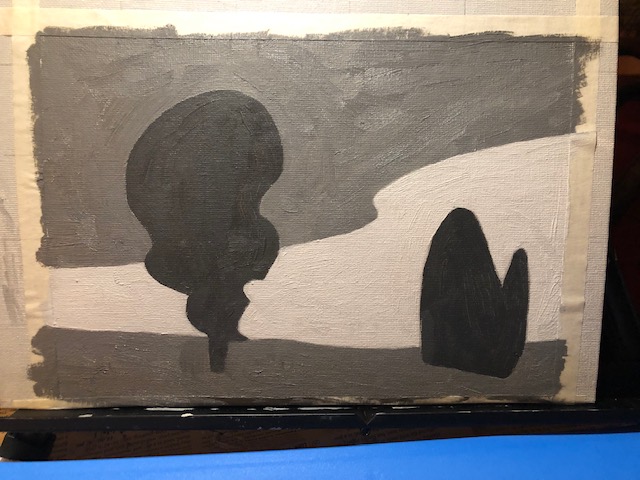

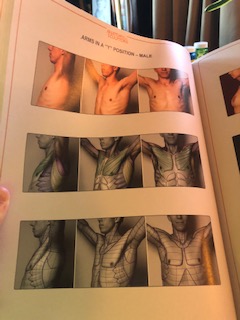

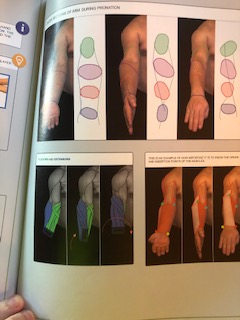

Anatomy for Sculptors by Uldis Zarins and Sandis Kondrats. This is the most money I’ve ever spent on a book. Ever. I think my fingernails were sweating as I pressed the order button. But I don’t regret buying it — what I regret is all the other ones I bought when I should’ve just pulled the trigger on this one to begin with. What I like about this book is that each area of the body is photographed in several different poses, and then each of these photo sets is repeated with the muscle groups overlayed in a particular color. This same color is used every time you see those muscles in other poses, so it really clarifies what’s happening when a particular muscle seems to be in the neck in one pose and the butt in another (perhaps a SLIGHT exaggeration). Like this:

There’s very little text or labeling here, but they do have helpful little asides throughout that help you understand some of the trickier areas. Like this:

Nope, still not getting it. But most people probably will. (As an aside: One odd thing about this book is that many of the women models seem taken from Pornhub [ahem — so I’m told] while the men have pixelated, um, parts. Personally, this latter fact doesn’t bother me — most likely I wouldn’t be drawing those parts anyway in my eventual goal of illustrating children’s books. But, FYI.)

Facial Expression and Portraiture

As much as I like Proko for anatomy, he really phoned it in with his portrait class. Honestly, it offered so little value above the free content that I actually wrote and complained. (And if they’d offered me anything other than excuses you wouldn’t be hearing about it now. KARMA.)

This category has one VERY clear winner:

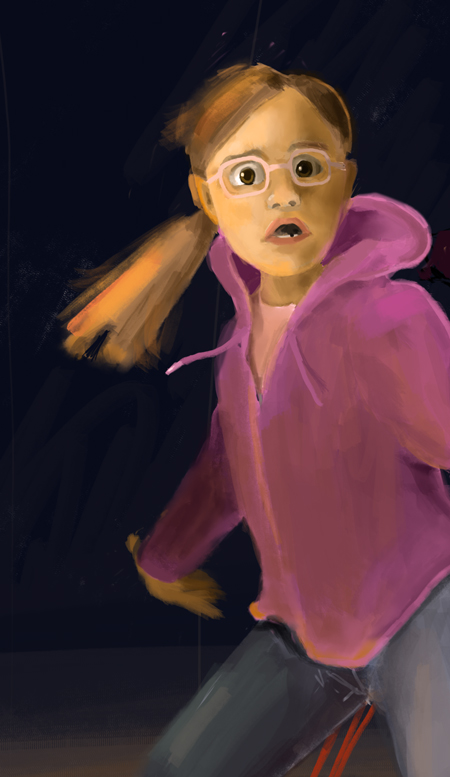

The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression by Gary Faigin. If you’re interested in narrative art, you MUST buy this book. If you’re interested in portraiture, you MUST buy this book. The beginning chapters break down each feature in great detail, with finished drawings that indicate how each is affected by age and sex. Later chapters break down how each feature is affected by the six basic emotions — sadness, anger, joy, fear, disgust, and surprise — and the nuances in between (the differences between horror and terror; between the [surprisingly similar] grief and laughter). In addition to the very finished portraiture examples, the author also includes an encyclopedia of emotions represented in more of a cartoon style, to really synthesize what each feature is doing in each expression. Ever been completely mystified by how the Pixar folks achieve those micro-expressions? It’s all in the facial muscles. This book will give you the key.

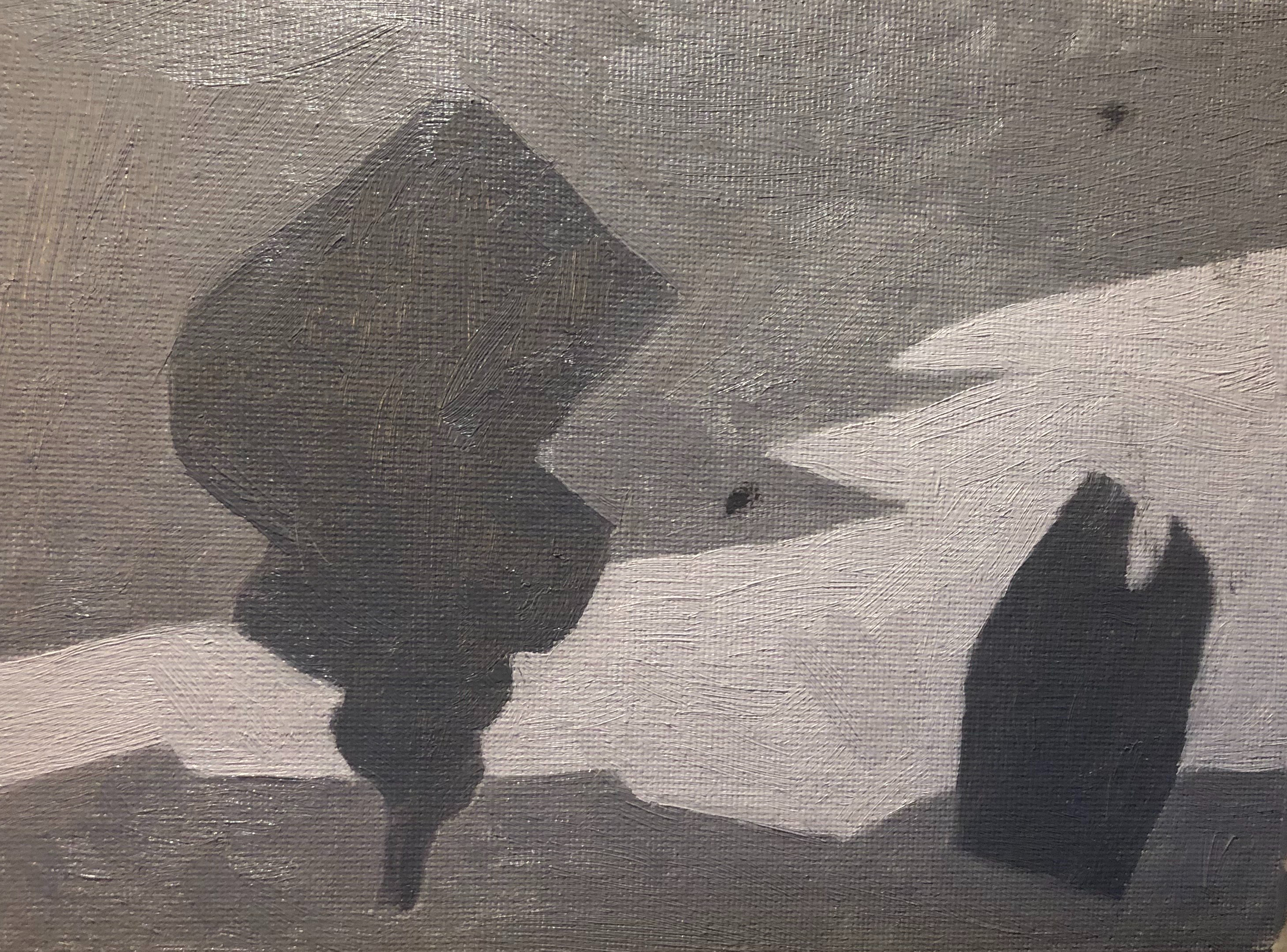

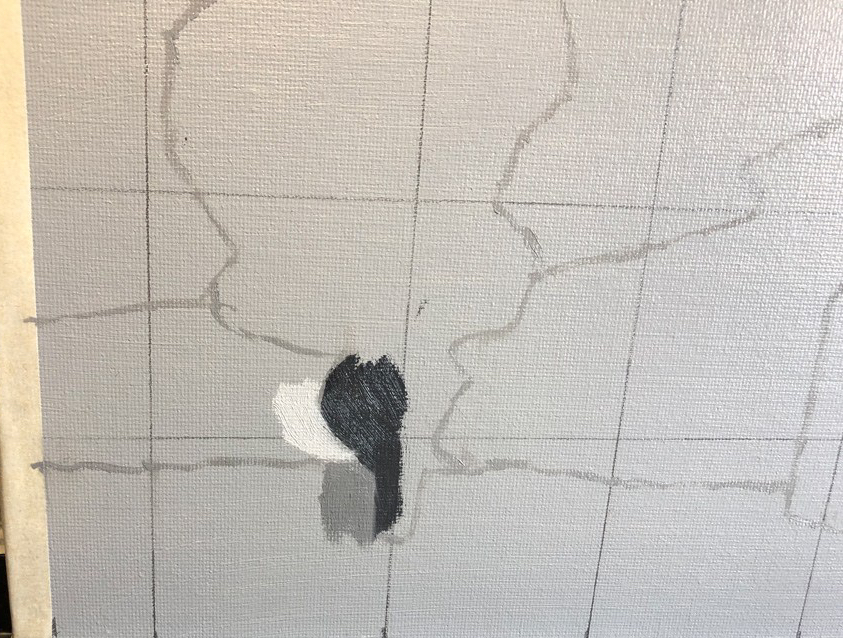

I’m currently leaning on this book heavily as I attempt to draw a picture of a girl jumping up after being frightened by a bear while camping:

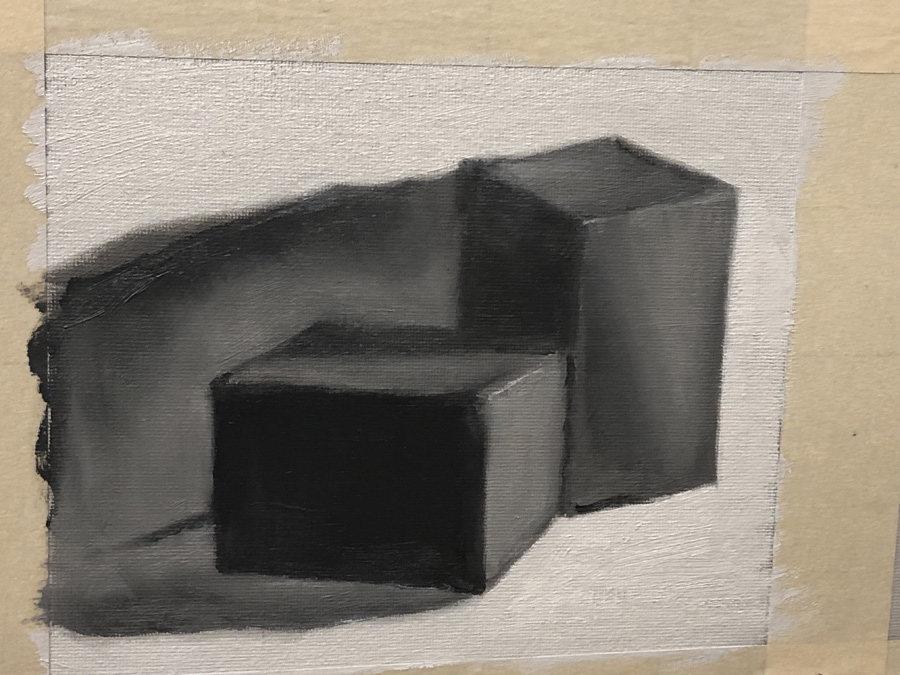

Lighting

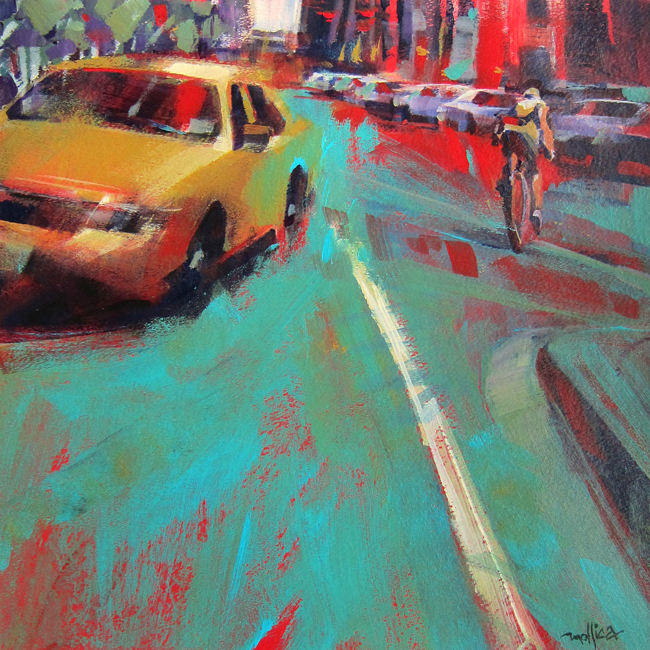

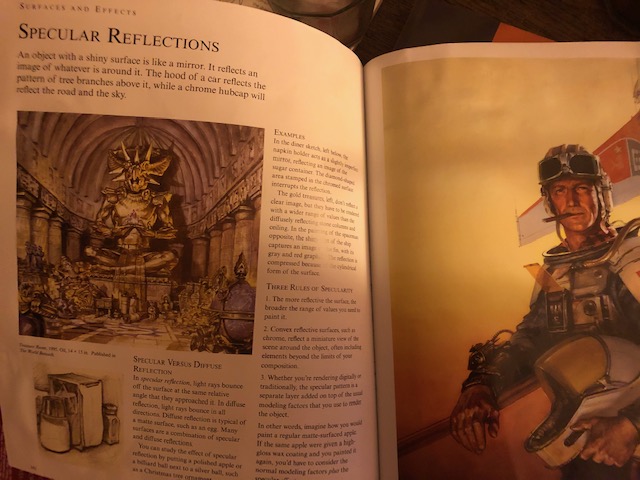

Color and Light by James Gurney. Once again, I feel like I’m choosing all of the books that everyone seems to know already, but there’s a reason a classic is a classic. Whether or not you appreciate Mr. Gurney’s style, he knows his stuff when it comes to lighting a scene. This book is geared toward painters, but the principles are applicable for anyone. It’s not a read-through book — more of an encyclopedia — but mine is already well-worn and I’ve barely begun in my “art journey.”

Each principle is allotted one page, with a smallish amount of text, and a few examples from the author’s own work. The writing is very accessible, and it’s brief and clear enough for you to completely absorb it when you’re in the middle of a project and looking for the solution to an art puzzle. While much of it is beyond what I’ll probably ever need, it’s answered all the questions I’ve had so far, and the rest is there when or if I’m ready. Drawing an underwater scene and want to understand how the light should be distorted? Don’t know where to begin with a limited palette? Gurney’s your man.

Alright, I’m going to be lame and stop here — breaking out my other suggestions to a Part Three. Apparently, I’m a prattler, and I’m also tired — after all, I’m now fift— now a little older than I was last week.

Stay tuned!