During the time when I was kept from the gym by my splinter (now healed), and kept from my studio by Jim’s admonitions on my light situation (now fixed), I was also kept from class by… well, there wasn’t any class. It was spring break (now over).

Since the assumption at The Art Academy seems to be that once you’re there, you never leave (there are people there who have been working on the same painting for years, apparently), there was no rushing to finish up the marble horse head paintings we were working on before we left before break; they were there waiting for us when we got in.

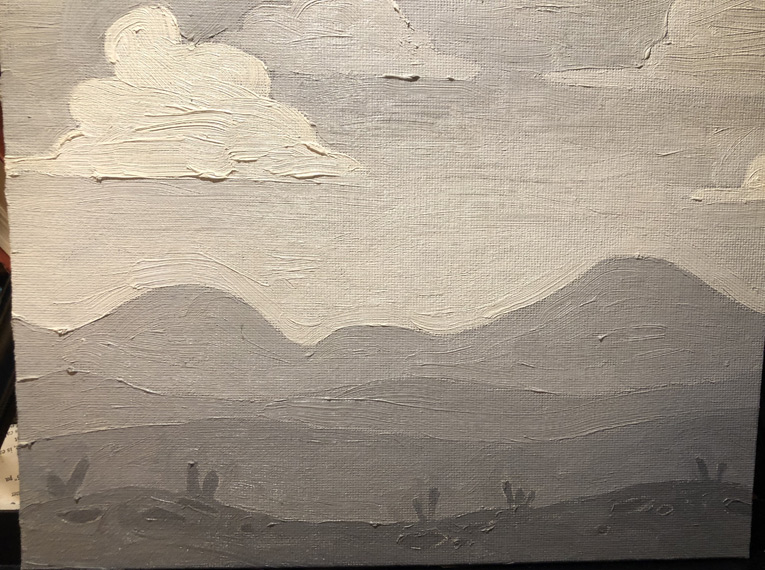

It was weird to go back to grey after my forays into color, but much much easier. I realized that I’ve been a bit lazy when it comes to color mixing at home — often I just mix something I think is in the ballpark and then go back and tweak it after the fact (that’s the beauty of oil painting — it’s incredibly forgiving). So I have been asking myself whether painting with color on my own is even a good idea — am I just teaching myself bad habits? I continue with it, though, because it’s fun, and ultimately, even if truly imperfect, I like the results much better — who wants to keep a grey painting? The last thing I want is to start feeling bored and uninspired — I figure, anything that keeps me painting on a regular basis has got to be for the best.

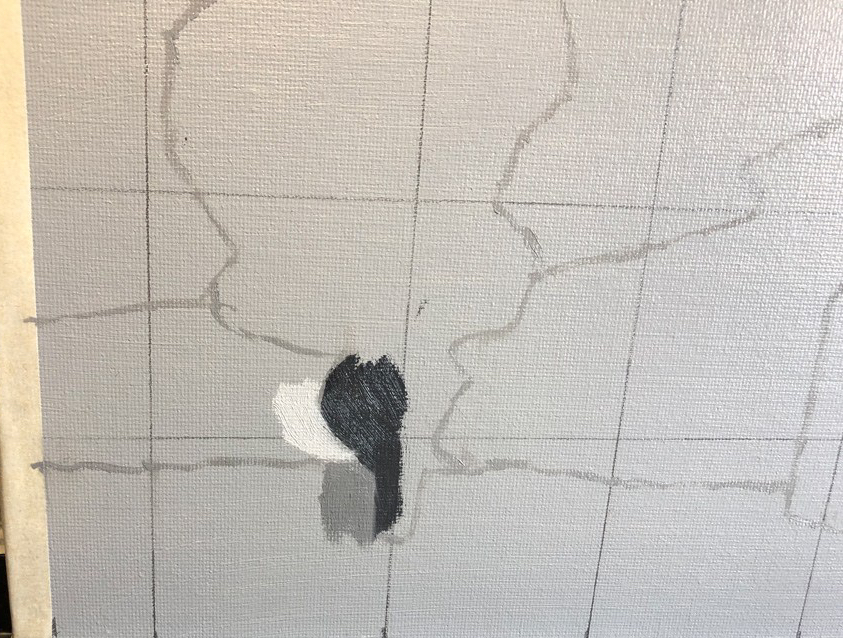

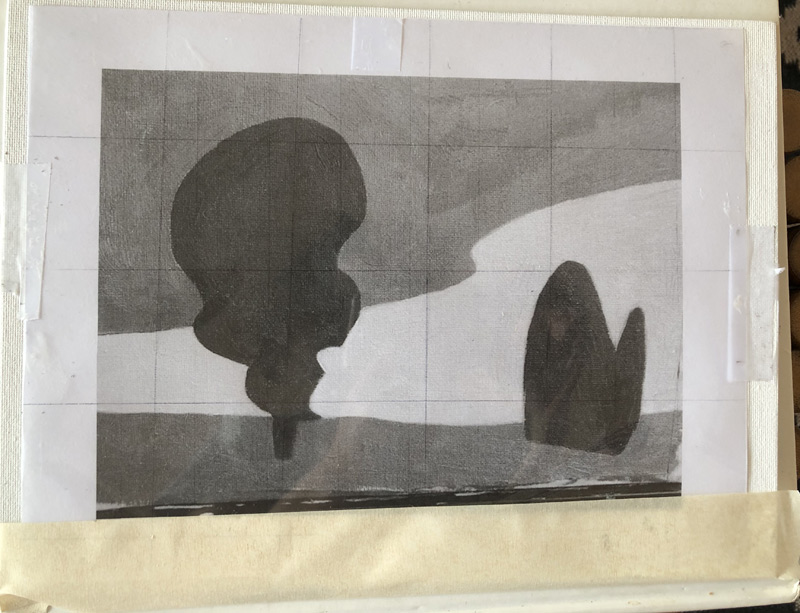

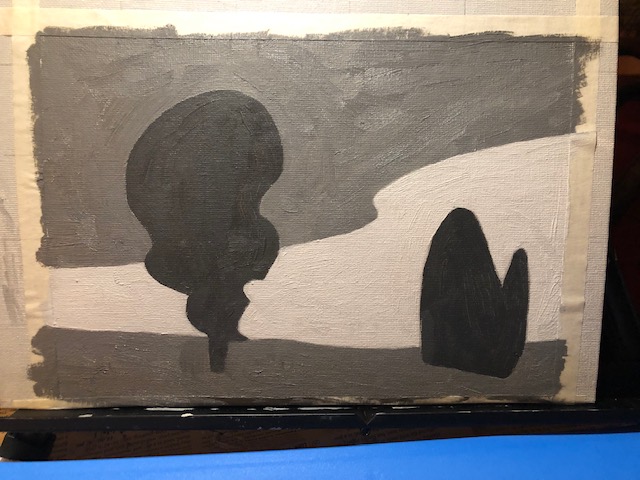

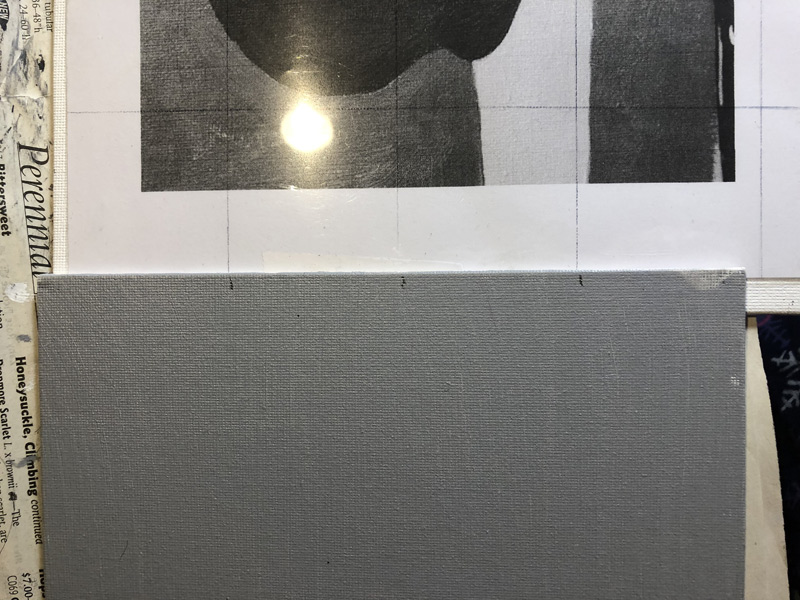

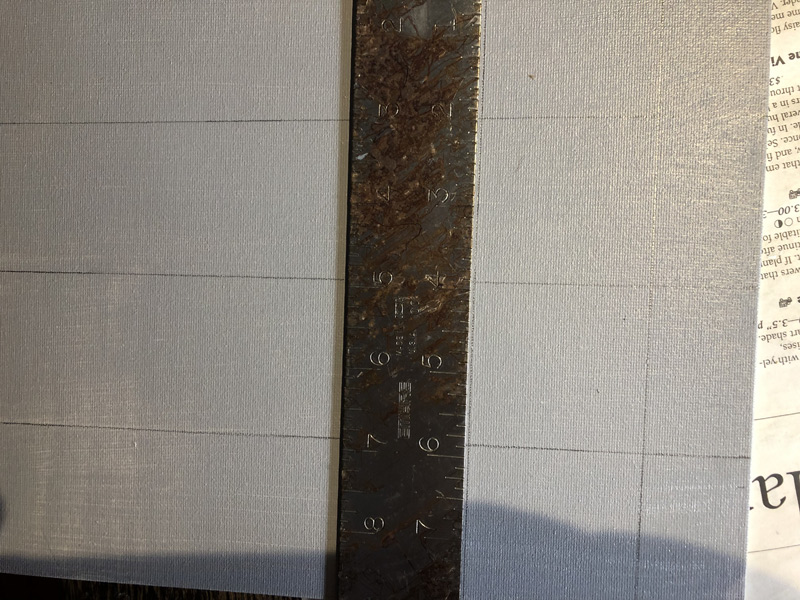

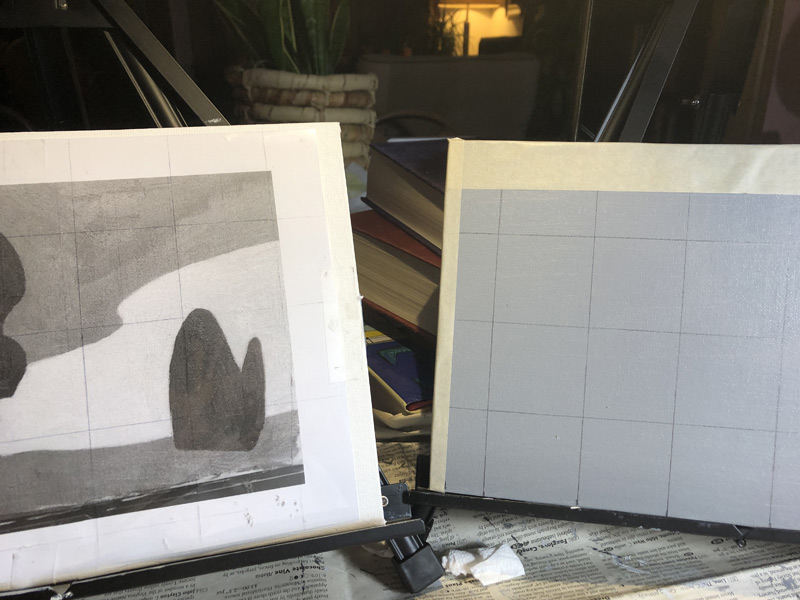

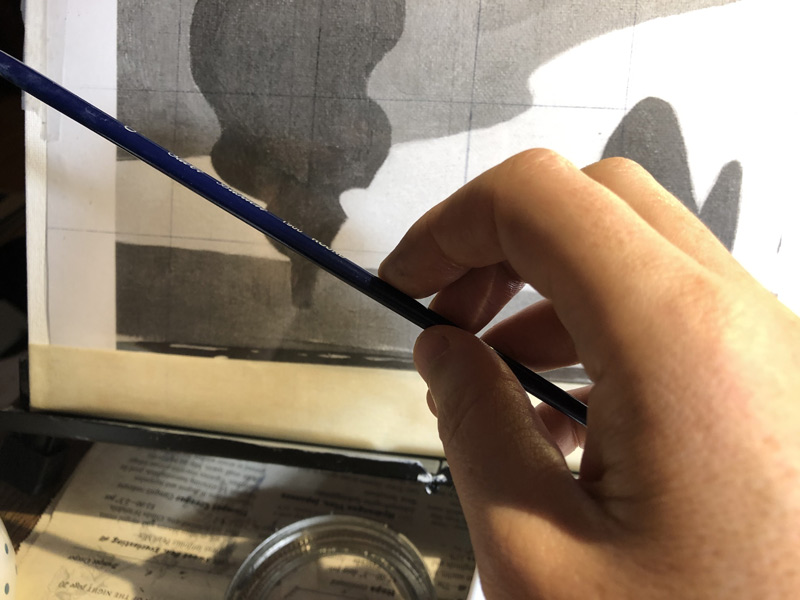

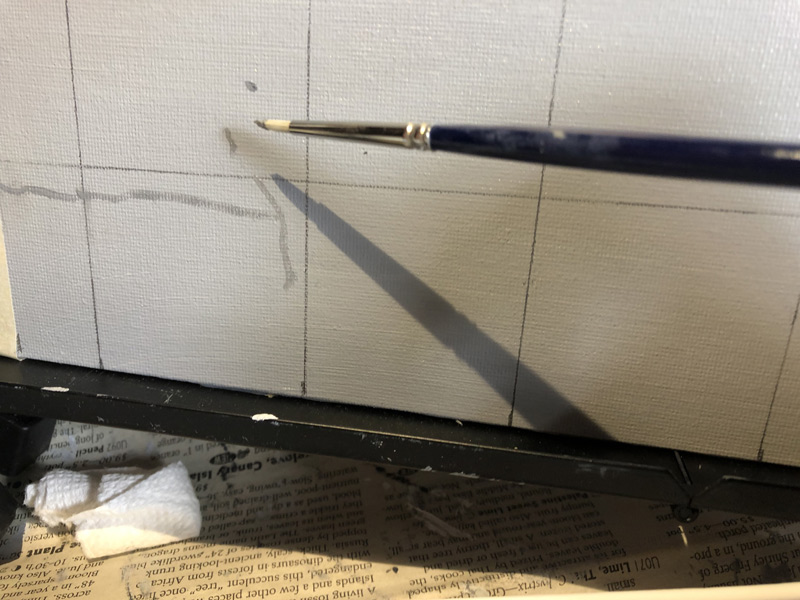

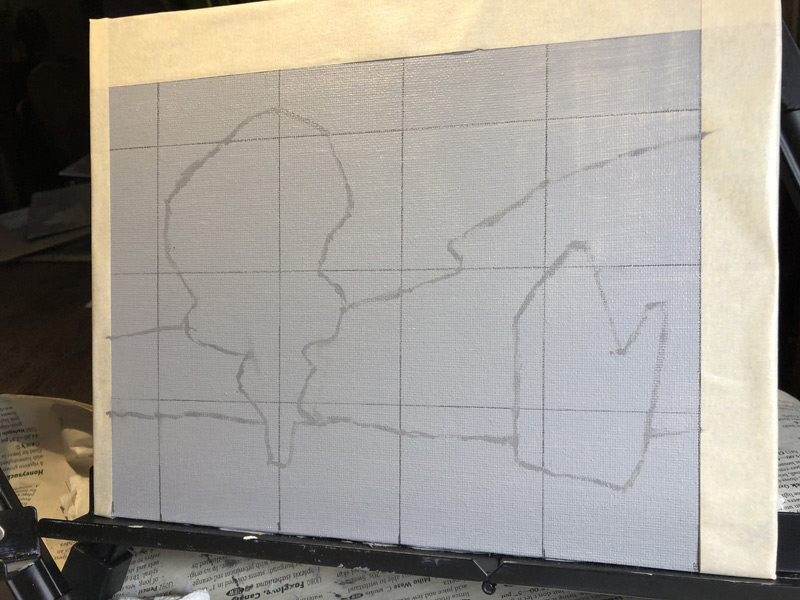

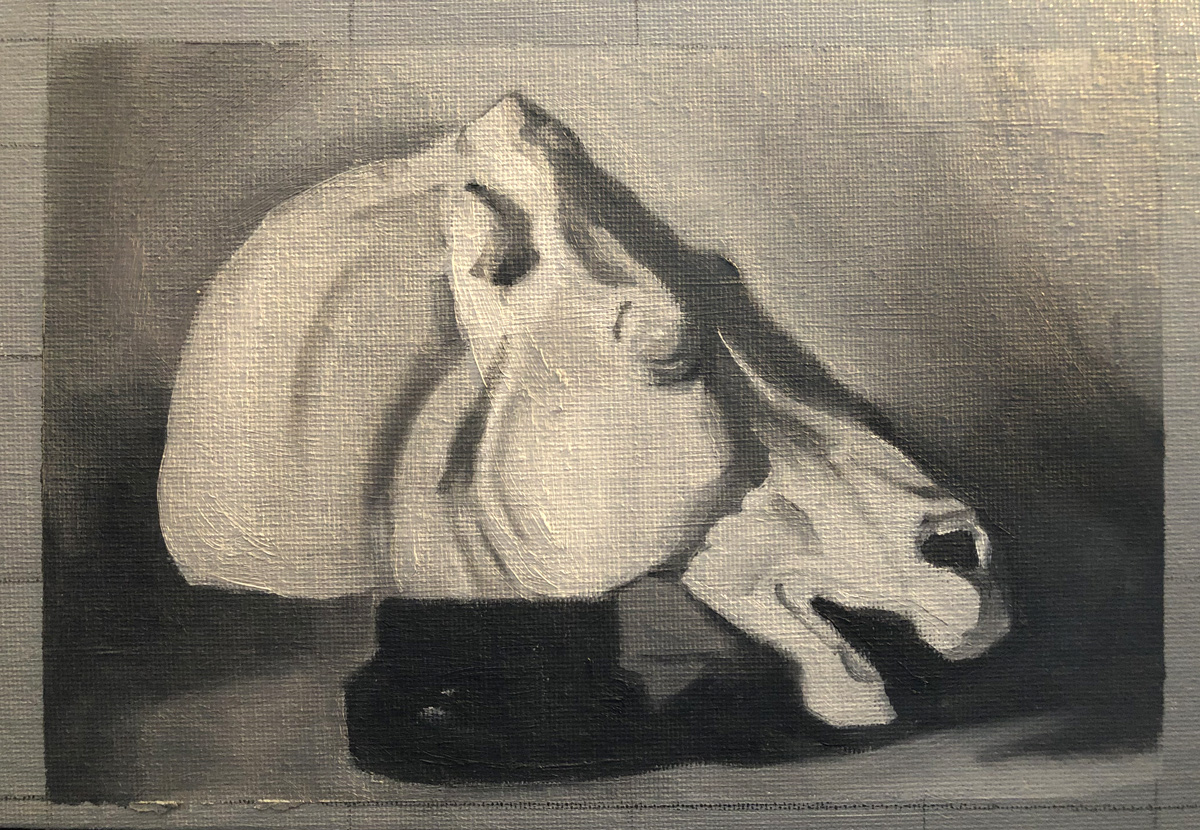

For this painting, we did what Jim called a “lay in”: We spent a couple of sessions painting the horse in a simplified form — blocking in the outline, background and some of the shading — and then our reference images were switched for others that had a lot more detail and we spent a couple more sessions painting those as well. The biggest issue I found was that in between session one or two of the detail work, I was given a different reference image (a common issue — I think they’re just handed out randomly in each class, and they’re all a bit different) and all the details were in different places than they were when I started them. This threw me for a loop, but Jim insisted that it really didn’t matter — ultimately, the exercise was just to practice recognizing and reproducing subtle values, as well as the process of first blocking in a simpler shape and then coming back to it for detail.

To me this felt like a big leap ahead from the box paintings we did for our last project, but completely manageable. Of course, I’ve obviously been painting on my own, but even if I hadn’t it would’ve still felt like the logical next step after shading and blurring. My nerdy self is still very excited by just how systematic this program seems to be. Looking forward to the next project!